Fay Jones and Frank Lloyd Wright:

Organic Architecture Comes to Arkansas

Frank Lloyd Wright and Fay Jones: Intertwined Careers

Gregory Herman, Associate Professor

- Department of Architecture

- Fay Jones School of Architecture

- University of Arkansas

- December 2014

WRIGHT’S USONIAN HOUSES

During his lifetime, Frank Lloyd Wright was known around the world for his innovative and beautiful designs for a wide variety of building types. He designed houses, office buildings, stores, and even entire cities. To this day, he is most famous for his designs for houses, which were varied in their size, scope, and cost according to the client for whom they were designed.

Wright’s professional career stretched across eight decades, and in that time, his house designs reflected changes in American social and economic structures, as well as changes in stylistic trends. In part as a response to the period of the Great Depression, during which he received few commissions, Wright was able to spend more time thinking about the possibilities allowed by emerging technologies in construction, and ways in which spaces for living could be reconsidered. Always searching for an architecture that was truly representative of his vision of America, Wright borrowed the name “Usonian” for his new house designs.

“Usonian” was a term coined by the nineteenth-century American author James Duff Law, who thought it more specific and appropriate than the term “American,” which could include all the countries of the Americas--north, south and central. Wright’s Usonian houses would be in the United States, “in Usonia”, and would thus be “of Usonia” as well.

Wright utilized all available progressive means for construction, and innovated some of them as well. Concrete block, long considered a lowly building material suitable for utility circumstances only, was used prominently and proudly in the Usonian house. Central heating, a common amenity in new construction by this time, was reconfigured in the Usonian houses as a radiant floor slab; hot water was circulated through tubing embedded into the concrete floors, making the spaces warm and comfortable regardless of the cold climate. Construction methods were kept simple, such that homeowners would be able to engage in much of the construction of their house themselves in order to assure greater economy.

Expressive of new ideas of domestic living space, Wright’s Usonian houses were small, but spacious feeling. Open living spaces and large expanses of glass allowed for interiors that seemed to blend into the adjoining exterior landscape. Wright designed built-in furniture for many of the spaces in the Usonian houses, thus making furnishings and architecture merge into a single expression. Like Wright’s designs for houses generally, the interior living spaces of the Usonian houses were centered on a large fireplace, symbolic of an age-old desire for unity and focus in a domestic environment. Stained wood boards fitted out the interiors of these spaces, making a restful, nature-infused setting for the rituals of domestic living.

A deep, shading roof overhang was typical in Wright’s houses; with so much glass, the Usonians needed this simple device as a means to counter the accumulation of excessive solar gain in the summer. Wright’s Usonian houses always included a carport: he had no fear of the dominance of the automobile in the modern world. To him, as to so many, the car symbolized the freedom of the individual.

The Usonian house thus represented Wright’s foray into modern, simple, economical housing – a custom response to a broad need, available to most anyone.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT AND FAY JONES

Fay Jones liked to tell of his first exposure to the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. As an adolescent, he chanced to see a newsreel at his local movie theater about Wright’s recently completed project, the Johnson Wax Headquarters, in Racine, Wisconsin. Impressed with the modernity and vision evident in the work, Jones knew then and there that he would pursue a career in architecture. Jones would look to Wright for the rest of his life as an idol, role model, and mentor.

Fay Jones first enrolled at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville in 1938. Interrupted by the onset of World War 2, he later resumed his studies in the newly formed Department of Architecture, graduating in 1950. Jones then moved to Houston to continue his studies at Rice University. Jones had first encountered Frank Lloyd Wright a year earlier, when both were in Houston attending the annual convention of the American Institute of Architects. At that convention, Jones was in the audience as Wright received the American Institute of Architects’ highest award, the Gold Medal.

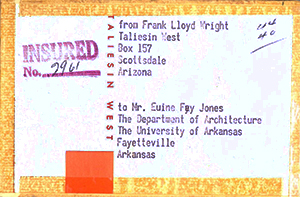

In 1951, Jones accepted a teaching job at the University of Oklahoma, where he taught until 1953. That year, Jones wrote to Wright, seeking employment. Wright had established a kind of school associated with his practice that he called the ‘Taliesin Fellowship.’ The Fellowship was conducted at Wright’s two offices, one in Spring Green, Wisconsin (‘Taliesin East’), and one in Scottsdale, Arizona (‘Taliesin West’). Those employed at the Fellowship were treated as students, and as such paid tuition to Wright, rather than receiving a salary, in exchange for room, board, and work experience with their famous master. Wright invited Jones and his family to visit Taliesin West for the Easter celebration in spring 1953. The visit was successful by all accounts, and that summer, Jones was invited to join the Fellowship at Taliesin East for a three-month apprenticeship. With his wife and young children in tow, Jones moved to Spring Green to join the Fellowship, during which he was schooled in the architectural principles promoted by Wright.

Jones returned to Fayetteville in fall 1953, where he joined the faculty at the architecture school, and also began his professional practice, always reinterpreting and extending the ideas put forth by Frank Lloyd Wright.

It had long been Jones’s desire to host Wright at the University of Arkansas. After many letters of invitation over the course of several years, Wright finally agreed to make a visit to Fayetteville in 1958, just a year before he died. Speaking to a packed crowd in the University’s Field House, Wright admonished young designers to see the world as he did, for its natural beauty, and for its ability to suggest an architecture that would embrace the natural world. He urged his listeners to look to the work of Fay Jones as an example of the sort of nature-connected architecture of which he approved.

Jones’s architecture shared many of the same sensibilities as Wright’s. Common to both was a belief in the primacy of nature as a provider of materials, form, and experience: wood and rock, minimally altered, provided the structural substance for their buildings, while glassy walls and deep overhanging roofs negotiated the limits of enclosure. Whereas Wright’s designs were usually configured with an emphasis on the horizontal, evident in almost any one of his Prairie Style houses, Jones’s work often embraced a distinctive verticality, as seen in his most renowned project, the Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas. While Wright considered nature as an earth-bound expression, Jones found his connection to nature in that which grew up from the earth. Perhaps the distinction came from Wright’s background – prairie bound, in awe of the horizon; Jones, a man of the hills, surrounded by rock ledges and forests.

During Jones’s career, he designed many buildings of note, including several innovative houses, as well as the famous Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, in 1980. Jones remained on the faculty until his retirement in 1988. In 1990, he was awarded the Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects in recognition of his distinguished design career, the same medal he had witnessed Wright receiving in Houston in 1949.

THE BACHMAN-WILSON HOUSE

With a completion date of 1954, the Bachman-Wilson house constitutes a late example of Wright’s Usonian houses. Abraham Wilson and Gloria Bachman-Wilson commissioned the house after a visit to Wright’s Shavin House in Chattanooga, Tennessee, where Gloria’s brother, Marvin Bachman, had served as a construction superintendent. Abe and Gloria’s written request of Wright: “Would you design a home for us?” His response: “I suppose I am still here to try to do houses for such as you.”

Still productive at age eighty-seven, Wright’s characteristically laconic response led nonetheless to a real design for the couple and their young daughter. The Bachman-Wilsons chose a site fronting the Millstone River within commuting distance of New York City. After a period of back-and-forth discussion of needs and desires, Wright proposed a design to the Bachman-Wilsons; its projected cost was more than double the original budget. With significant adjustment, a final design was agreed upon, and construction at the site began.

Some aspects of the Bachman-Wilson design were selected for economy. Concrete block was used extensively, where more expensive brick had been initially proposed. An elongated single-floor plan was truncated by stacking on a second level, thus compacting the mass of the house significantly. The views to the adjacent Millstone River were reserved for those inside the house: the street-facing side of the house was made private by a solid masonry wall, articulated by the entranceway, thus allowing the view to be revealed as one entered the living space.

Wright’s characteristic Usonian treatment was evident throughout the house: open living space, built-in furniture, a central hearth, all wrapped in a woodsy frame including large expanses of glass and a strong overhanging roof. The main level included all primary living spaces: a kitchen, a dining area, a living space, and a guest room / study, along with a small bathroom and a utility space. No basement was included. The upper level of the house was accessed by a light and simple stairway, hung from steel rods, and included two bedrooms and a bathroom. Balconies outside the upper level rooms provided visual connection to the level below. Connection to nature was made more emphatic by the inclusion of several French doors along the glassy wall of the living space, leading out to the river and the wooded landscape beyond.

Among the most striking components of the house were the pierced wooden panels installed high above the French doors in the upper reaches of the living space. These panels and their geometric jigsaw designs lent an ornamental elegance to the space. More significantly, the pierced panels let in a distinctive pattern of light and shadow, changing with the sun’s path throughout the year.

Beautiful as the setting was, the proximity to the Millstone River, with its periodic tendency to flood, threatened the house several times. After acquiring the house and lovingly restoring it, only to see it once again inundated by the Millstone’s floodwaters, recent owners Sharon and Lawrence Tarantino decided that moving the house (as a provision of its sale) would be a good strategy for ensuring its survival, albeit on a new site. In 2013, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, announced that it had acquired the Bachman-Wilson house, and that it would be reassembled on a new site, nestled in the trees on the museum grounds in Bentonville.

The site chosen on the museum grounds, while differing in solar orientation from the original siting in New Jersey, was positioned such that the house’s orientation to the adjacent Crystal Creek would recall the former siting along the Millstone River. Upon completed reconstruction, the Bachman-Wilson House will stand as the only building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in Arkansas.