Family Photo Album by Bobby C. Martin

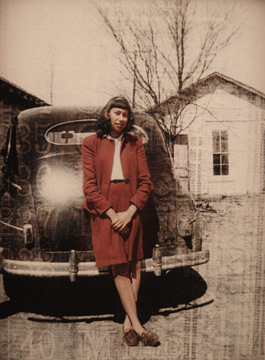

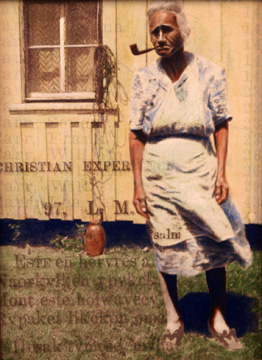

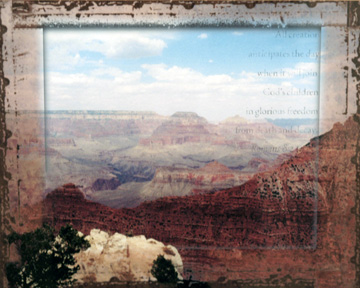

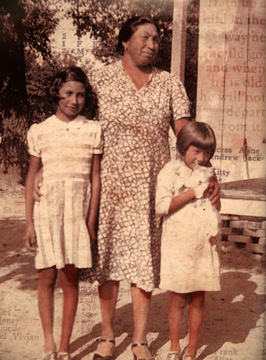

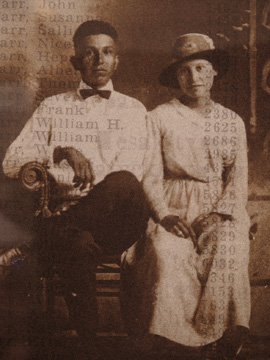

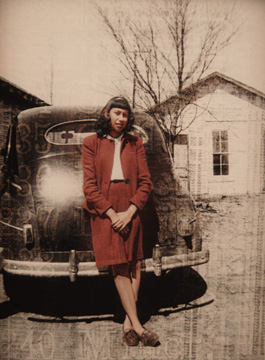

Bobby C. Martin's “Family Photo Album” is not your typical photo album, in part because Martin's family is not the typical American family and in part because Martin uses his considerable artistic talent to transform these personal images into haunting cultural symbols of Native American's assimilation into mainstream America.

Muscogee (Creek) artist/designer Martin, who earned degrees in both painting and printmaking, incorporates unexpected techniques when creating his images. Martin says, “My art is about history'”family history, cultural history, political history'”as seen through the time-blurred filters of old family photographs.”

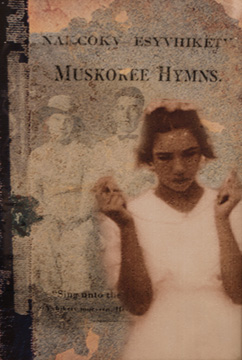

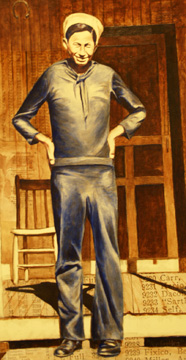

He typically begins with a photograph'”for example, Uncle David standing on the front steps in the blue sailor uniform of the U. S. Navy'”then superimposes onto this image various snippets from documents that themselves symbolize the dominant majority's whole-scale reordering of Native American culture.

Thus, in the image “Uncle David Killed in Action 1944,” lines of text from the Dawes rolls and the Muscogee (Creek) Christian hymnal appear on the screen door, the clapboards, the steps underneath Uncle David's feet. The old home place in front of which Uncle David poses, smiling with arms akimbo, thus becomes permeated with and forever marked by the majority's rewriting of the culture of the Muscogee nation. The sad fact of Uncle David's early demise in the defense of the United States is made more poignant and even ironic as the ghost texts transform Martin's family history into a larger story that encompasses the histories of all those individuals who, reluctantly or willingly, crossed the cultural line. Martin says, “There's the history of Native American people and their relationship to the government, and the situation of Indians in boarding schools, Indians in the Christian church, all these layers.”

Another baffling yet delightful incongruity appears in “Sequoyah County Champs 1917.” The image depicts the victorious basketball team of that year from Dwight Mission, the oldest school in Oklahoma, which was established on Sallisaw Creek in 1830 after the forced removal of the Cherokee peoples from Arkansas. The image of the unsmiling team posing for the photographer deviates from the norm of the era in so far as the Native American team members are all wearing matching headbands and Indian blankets over their uniforms rather than letter jackets, a brief glimpse of the old culture in the midst of the new. Superimposed behind this image is a section from a monument in the mission's cemetery that memorializes thirteen boys who were killed at Dwight in a tragic fire, as well as names from the Dawes rolls and a brief passage from the Psalms.

Another image, “Dwight Mission Lawn Tennis Team,” shows a similar grouping of Native American students dressed in white tennis outfits. Martin says, “The ironic imagery suggests that because you dress up somebody, in this case Native Americans, in spiffy tennis outfits, they become civilized. The fact is that they were already civilized.”

Martin was born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma in 1957. After an early career as a musician and recording studio owner, Martin turned to visual art and returned to school. He received a BA degree from Northeastern State University in 1992, and an MFA in printmaking from the University of Arkansas in 1995. While at Arkansas, Martin was awarded a Professional Development Fellowship from the College Art Association that led to his employment as graphic design coordinator at the Gilcrease Museum in 1995. Currently, Martin is an associate professor of art and Art Program Coordinator at Northeastern State University in Tahlequah.

Martin's artwork is exhibited and collected internationally. His work has been featured in exhibitions ranging from “Who Stole the Teepee,” a traveling exhibition organized by Atlatl, Inc. and the Smithsonian Museum of the American Indian, to “Something More Than '˜Art': Handworks by American Indians” held at the Utsunomiya Museum of Art in Japan. His work is in the permanent collections of the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, the Southern Plains Indian Museum, Philbrook Museum and the Gilcrease Museum.

For a complete exhibition record and curriculum vitae, please visit www.bobbycmartin.com. “Family Photo Album” will be on display in Mullins through the end of December. For more information, call 479-575-6702

(Click thumbnail image to enlarge.)