The Spirit of Missions: Christian Colonization of Territorial Arkansas

This exhibition examines the history and first-hand accounts of interactions between Christian missionaries and Native Americans in the Arkansas Territory in order to help more fully characterize the cultural interactions of Arkansas' history.

Religious and cultural exchange has occurred between European colonizers and native peoples since Columbus first landed in the Americas in 1492. But any act of colonization is not merely a physical or territorial one and never plays out solely in terms of land and resource acquisition. The inevitable mixture of peoples, religion, and culture between colonizer and colonized means that the economy of colonization stands ever hand-in-hand with the culture of colonization.

Christian missionaries were always at the forefront of colonization efforts, and the mission to convert native peoples to Christianity was a staple policy among leading colonial nations. Beside every conquistador stood a Christian, and it was standard to ensure that the first foot ashore in the New World carried a gun while the second carried the Gospel. Though secular colonial powers sought economic wealth and resources, famed 16th century Spanish historian and friar Bartolomé de las Casas argued that “Christ seeks souls, not property” (In Defense of the Indians, 1548).

This missionary zeal and desire to spread the Christian Gospel never disappeared because it is fundamentally and inextricably tied to the culture of Western colonization, and so similar missionary endeavors seen first in the Spanish and French colonization efforts of the 15th to 18th centuries can be seen even in America’s heavily driven westward expansion during the 19th century. The Louisiana Purchase (1803) opened up a massive area of land for American territorial expansion, and of course, one of these territorial lands was the “Arkansaw” Territory, organized in 1819. Since its very earliest days, the Arkansas Territory saw the immigration and residency of multiple Native American tribes, many of them relocated from east of the Mississippi River as a result of treaties signed with the US government between the 1810s and 1830s.

The missionary spirit came to Arkansas shortly after these relocations with a zeal to educate and convert the Native American people. These efforts resulted in a unique cultural and religious clash between the missionaries and Native Americans which called into question the nature of their interaction and how each side conceived of the other. This exhibit looks at some of the history and first-hand accounts of these interactions in an effort both to better characterize this clash of cultures as well as to paint a more complete historical picture in the gallery of Territorial Arkansas.

(Click thumbnail image to enlarge.)

Frontispiece of the Captivity Narrative of Hannah Lewis (1817)

E87.L48 L48 A popular form of literature in the United States from the 17th to late 19th centuries, captivity narratives usually tell the story of a person (usually “civilized” or white) who is captured and taken prisoner by a less-civilized (and usually Indian) enemy. These tales very conspicuously draw out and play off of the reader’s sense of “we” against a sense of the “other,” very frequently employing derogatory language to describe Native Americans.

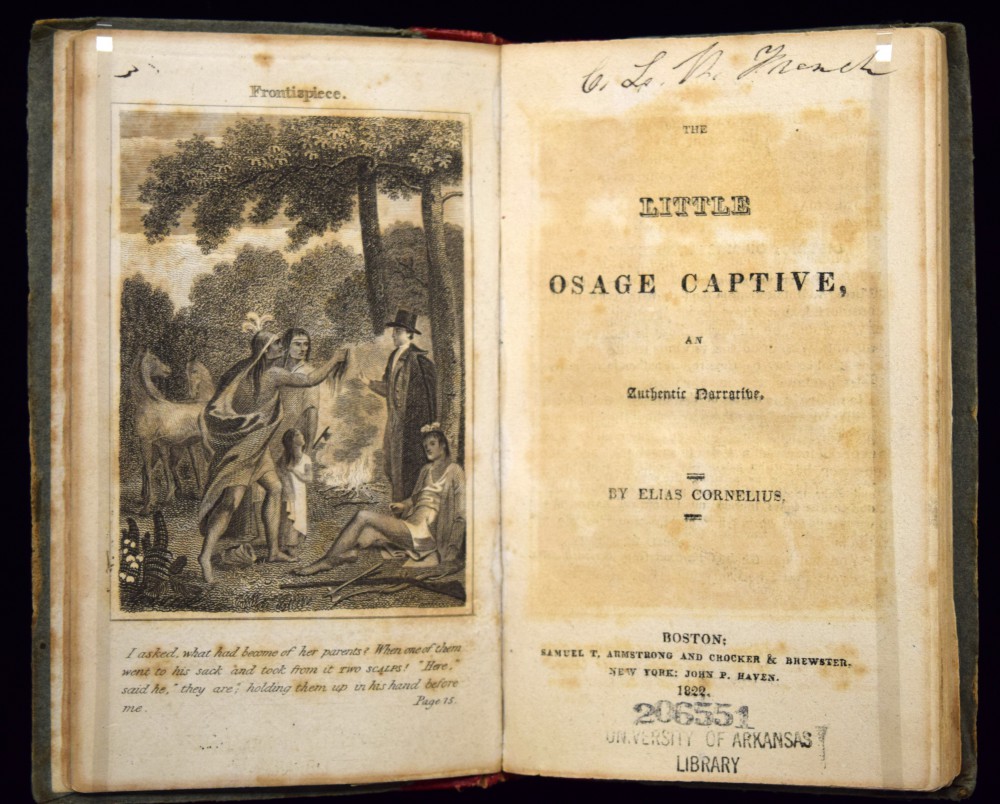

Frontispiece and Title Page of The Little Osage Captive (1822)

E90.C3 C77 Written by missionary Elias Cornelius (1794-1832), The Little Osage Captive was published to serve a similar purpose as that of the narrative of Catharine Brown. Though this work is oriented more towards children, it nevertheless sought to “enkindle their zeal in the missionary cause.”

Page from Rev. Cephas Washburn’s Reminiscences of the Indians (1860)

MS W25 An excerpt from the autobiographical narrative of Rev. Cephas Washburn (1793-1860), Presbyterian Minister and founder of the Old Dwight Mission near present-day Russellville. Sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to found a mission among the Cherokee, Washburn sought to provide education and spiritual support to the Cherokee, especially those recently relocated by the Treaty of Turkeytown from east of the Mississippi River. This excerpt illustrates Washburn’s first experiences with Dwight Mission, which he had only just established in 1820. Washburn served as the prime Native American missionary in Arkansas until 1850, when he resigned to serve as minister of the First Presbyterian Church in Fort Smith. Washburn is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.